- Home

- Brian Dickinson

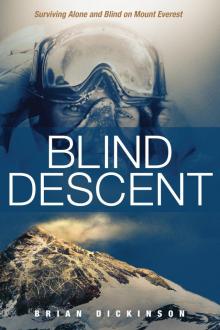

Blind Descent Page 6

Blind Descent Read online

Page 6

The kids crowded into the screen, talking over each other.

“Daddy, we got to go to the beach!” Jordan said.

“It’s so warm here,” Emily chimed in.

I pictured them swimming in the Pacific while I donned more layers and hiked into the cold heights of the Himalayas.

All too soon my battery was running low and it was time for the kids to go to bed. I was so glad to talk to my family, but as soon as I hung up, a wave of sadness overcame me. I wanted to cry, but the rest of the climbing team was in the dining area, lying on the benches and getting some rest. I didn’t want to embarrass myself, so I just closed my eyes and took a deep breath. Thank you for my family, God. Thank you that you’re taking care of them even when I’m far away.

After tea and lunch, we set out across an extension bridge that was stretched high over a raging river. But we had to slow down our pace when a traffic jam formed in the middle of the bridge. Our yaks had stopped on the four-foot-wide bridge and wouldn’t budge. When a trekker attempted to continue across the bridge, one of the yaks charged him. The other animals refused to cross with their heavy loads. I’m certainly no yak whisperer, but they could have been resisting because they knew there was a two-mile hill with a 2,000-foot elevation gain on the other side.

The Sherpas tried pulling the yaks, whipping them, and even throwing rocks at them, but the animals were stubborn. They expressed their displeasure by kicking at anyone who came close to them. Finally, after much coaxing, the Sherpas bribed them across from the other side with food.

Once we got across the bridge, I took off ahead, letting the rest of the group know that I’d wait for them at the top. I listened to a mix of Casting Crowns songs while I hiked. As someone who lives in two very different worlds—the world of an extreme athlete and the world of someone with a strong faith in Christ—I’ve always loved the song “Here I Go Again.” Climbing Everest was already giving me opportunities to conquer my fears and share what I believed, and I wanted to take advantage of those chances.

That old familiar fear is tearing at my words

What am I so afraid of?

The hill switched back and forth, with a couple of areas of off-trail climbing that required me to go straight up. I chose the most direct path and made it to the top of the hill in about 45 minutes. The top of the rise was a little more exposed to the elements since it was outside the tree line, making it windy and cooler, with occasional snow dustings. I found a flat rock to sit on and added an entry in my journal, which I wrote in daily.

I also reread the words JoAnna had written in my journal before I left:

You’d better come home, because you mean the world to me! I want to grow old with you and spend the rest of our lives together. Don’t forget to read your Bible and pray—I know God will guide you just as he’ll be guiding me here at home. He has a plan for your life, and I believe you will come home safely. Summit or not, please come home to us safely. Enjoy your time, cherish every beautiful moment, and we look forward to seeing you in nine weeks or less. I love you so much!

After about an hour, the rest of the trekking group arrived. We visited the Tengboche Monastery, one of the highest monasteries in the world. The monastery was originally built by Lama Gulu in 1916, but it has been rebuilt several times after being destroyed by earthquakes and fires over the years. We removed our hiking boots and entered through the small door. Once inside, I was met by the strong scent of incense. I watched monks dressed in burgundy robes lighting candles and chanting in Nepalese.

It started to snow lightly as we headed down from the monastery and toward a village called Deboche. On the final leg of our journey for the day, we made our way through a tunnel of pine trees and towering rhododendron shrubs. After walking beside me for a while, Pasang told me, “You are very strong. You will have no problem climbing Everest.”

I found his comment to be reassuring, but I knew that being strong is only one piece of the puzzle. It’s all about how your body does at high elevations, if you can avoid sickness and injury, and if the weather cooperates. So many variables are out of your control, and there are times you have to remind yourself of one of the cardinal rules of mountaineering: if things don’t work out, the mountain will always be there tomorrow.

We stopped in Deboche for the night, and I noticed that the farther away we got from civilization, the smaller the rooms were getting and the fewer accommodations we had. I paid a few bucks to take a shower, and when I did, I realized that the little instant shampoo tablets I’d purchased were pretty much worthless. They turned into mushy paper, hardly producing a bubble, and I spent more time scraping the sludge from my hair than getting clean. At least the water was relatively hot, and it felt good to zone out under the light water pressure from the showerhead. The 10 minutes of hot water I paid for were over in a flash, and I grabbed my towel to dry off as quickly as I could. I put on clean underwear, but the rest of my clothes were the same ones I’d been wearing earlier. I alternated between a few pairs of socks, two pairs of underwear, a few shirts, and a couple of pairs of pants, which I would hand wash whenever we had a rest day and clear enough weather for them to dry out.

That night at the teahouse, I had my normal dinner of soup and pizza. I was relieved that all the villages seemed to have pizza as a dinner option. The cooks used dried yak dung for fuel over their fires, and I had no guarantee that they would wash their hands, but I’d do what I could to limit my chances of food poisoning. I ordered a Mars pie for dessert, which was basically a Mars bar cooked inside a breaded tart. It was no Chips Ahoy! chewy chocolate chip cookie, which is my vice of choice back home, but it was a nice way to end a successful day of trekking.

That evening we were all asked to keep quiet in the dining area because a group from the Dominican Republic was doing a live video feed for CNN. They were the first team from their country to summit Mount Everest, and the excitement in the air was palpable. I found out later that Karim Mella and Ivan Gomez were successful in their attempt and ended up being the first Dominicans to make it to the top of the world.

Later that night the group started talking about the most famous legend of the Himalayan region: the yeti.

“So what’s the real story about the yeti?” one of the climbers asked the Sherpas in our group.

From the reading I’d done before my trip, I knew that Western explorers in the 19th century had returned home with tales about large, apelike beings. But the yeti has been part of Nepalese culture dating back many centuries before that.

As Sherpas from different regions offered descriptions of the yeti, I quickly realized that while the specifics of the legend vary from region to region, everyone had grown up surrounded by some kind of cultural lore about the abominable snowman.

“It’s a wild man,” one of the Sherpas said. “Like an ape.”

“No, it’s a cattle mixed with a bear,” said another.

Another Sherpa painted a different picture: “It’s a glacier being that hunts,” he said. “It is very powerful, like a god.”

As I lay in bed that night before our final trek to base camp, I wasn’t afraid of the yeti. I wasn’t afraid of the high altitude. I wasn’t afraid of Mount Everest. I wasn’t afraid of what this climb would demand of my body. I had only one fear: that something would prevent me from returning home to tuck my children into bed again.

As I drifted off to sleep, I took comfort in knowing that while Everest might loom large and so might my fears, God was even bigger. Joshua 1:9 says, “Have I not commanded you? Be strong and courageous. Do not be afraid; do not be discouraged, for the LORD your God will be with you wherever you go.”

Wherever you go. Even if it’s 29,035 feet above sea level.

CHAPTER 3

VILLAGE HOPPING TO BASE CAMP

You make known to me the path of life;

you will fill me with joy in your presence,

with eternal pleasures at your right hand.

PSALM 16:11

ON THE MORNING of April 8, sunlight peered through the window as roosters crowed outside. I got up and packed my expedition bag and then went out to enjoy the sunshine.

It was my mom’s birthday, and I wondered what she was doing 7,000 miles away in Kailua, Hawaii. She and my dad had moved there recently to take care of my grandmother, who had had a stroke. They were planning to stay in Hawaii for a while to make sure she was taken care of. Once she was settled, they’d move her into a nursing home on the island and return home to southern Oregon.

I set up my solar recharging battery pack to take advantage of an hour of sunlight before we left for the next village, Pheriche. As I unraveled my solar panels, a female trekker from another group bent over and let one go right in my direction. We both laughed, but I still stepped away in search of clear air.

Flatulence is one of the lesser-known hazards of high altitudes. High elevations cause increased pressure in the stomach, which in turn must be released. Among climbers, the condition is known as HAFE, for High Altitude Flatus Expulsion (a play off of HACE, or High Altitude Cerebral Edema).

The trip was already starting to get interesting.

The leg of the journey from Deboche (12,400 feet) to Pheriche (14,000 feet) wasn’t very difficult, as it was just a long, gradual climb. The Sherpas wanted to make a stop along the way at a monastery in Pangboche to participate in a puja—a good luck ritual. As a Christian, I was committed to worshiping God alone and not bowing down to false idols, as the Bible talks about in 1 Corinthians 10. But I also knew that this was important to the Sherpas, and I respected their right to follow their own religion.

We dropped our packs outside, near four-foot piles of drying yak dung, and ducked through a low doorway to enter the monastery. According to tradition, a puja ceremony is performed before climbers attempt a summit. White silk scarves are tied around the climbers’ necks, and a monk throws rice in their faces.

The ceremonial lama who was leading the puja, Lama Geshi, was battling a nasty head cold. He kept blowing his nose and coughing throughout the ceremony, and I was worried about catching a virus. I tried to take every precaution to avoid illness, but sometimes your immune system is breached by situations you can’t avoid. I held my breath as much as I could, but at that altitude, I didn’t last long before I had to come up for contaminated air.

When it was all over, I said a prayer, thanking God for being the one true God and asking him to keep our group healthy.

When we left the monastery, we were met with a lingering odor that smelled like a cross between a gun range and feces. The main source of fuel in the area was dung that people burned, so there were heaps of yak droppings left everywhere to dry out in the sun. And since the Sherpas used yak, dzo, and donkeys to carry supplies through the valley, the trails were littered with animal waste.

“If you breathe in too much dung, you get Khumbu cough,” Naga told us. “You cough so much you break some ribs.” Naga was one of our Sherpa trekking guides, and I had no doubt what he said was true. I put on the buff to cover my nose and mouth to prevent as much dust and decaying animal waste from entering my lungs as possible.

After a few hours of trekking, we reached Pheriche and unloaded our bags at the Himalayan Hotel, where we’d be staying for two days to help everyone acclimatize. Each room had two beds, and there was one bathroom on each floor. The bathrooms had no lights—a luxury I hope I never take for granted again. There was a shower available if I wanted to pay for it, but I figured I could last a few more days before my personal stench got the best of me.

The next day a couple of our group members were battling altitude sickness or stomach issues, so we mostly took it easy. But I was feeling strong, so I decided to climb higher to continue my acclimatization process. I was also hoping to get a phone signal on the hill since it had been a few days since I’d spoken to my family. Before I left, I’d told JoAnna not to worry if she didn’t get a call from me every day since signals could be spotty. She told me later that every time her phone rang, she ran to it, hoping it was me, but it rarely was.

I went for a hike with Pasang up to about 15,000 feet, where we got a great view of Island Peak (20,305 feet). At the top of the hill I was able to get a cell signal, so I made a quick call to JoAnna. We knew we wouldn’t have long to talk since we’d likely lose the signal soon, but it was worth the entire climb just to hear her voice. Her life was still in fast motion, and she had so much to fill me in on, while mine was the complete opposite. I knew it felt like a bit of a tease for her to hear my voice and then not be able to talk long, but we squeezed in as much as we could in a few minutes.

“Jordan has been acting out lately,” JoAnna told me. “And both kids have been having nightmares since you left.” For a moment, I wondered if they were having premonitions in their dreams, but I couldn’t let myself dwell on that thought long.

While we were up on the hill, I was also able to take some photos for my sponsors with the Himalayan peaks in the background. I held up banners with their logos as Pasang took rapid-fire shots with my camera.

As we descended down the loose scree of rock, Pasang said, “You are a super strong climber. You and I will be standing on the top of Everest in a month.”

I loved his confidence.

•

Back home I’d heard about famous climbers in publications like Climbing magazine and Outside magazine, but now that I was on an Everest expedition, I had the chance to meet some of them in person. A number of them were even staying in the same hotel I was in. One evening I talked to Willie Benegas, who holds multiple speed ascents on various peaks, and his brother, Damien, who were leading a group on the south side of Everest. They were attempting to be the first to summit all three peaks in one trip—Nuptse, Lhotse, and Everest. I later heard that Willie flew out of Everest base camp back to Kathmandu to get his eyes checked out.

Neal Beidleman passed through while we were there too. He’s best known for his heroism during the 1996 tragedy, in which he stayed in the whiteout blizzard with his clients all night in the death zone. This would be his first time climbing Everest since the tragedy. I also met Mark Tucker, who had climbed Everest in the 1980s for a peace climb with representatives from Russia, China, and the United States. This time he was there as the base camp manager for Rainier Mountaineering, Inc. In base camp and Camp II, our group would be positioned next to the group led by Mark and Dave Hahn, who had summited Everest fourteen times—more than any other non-Sherpa climber.

The last night in Pheriche, I played a few games of hearts with Mark. Over the span of many expeditions, he’d spent considerable downtime sharpening his card-playing skills. He thought he had me figured out using deductive reasoning, but in the end I won the last round based on pure luck.

As we talked, we discovered that our plans for the trip were pretty much perfectly aligned. We were using the same Sherpa outfitter, Kili Sherpa, and we’d be attempting the same route.

After our last round of hearts, Mark stood up. “Well, it’s time for me to turn in,” he said.

I stayed up to listen to some local Nepalese music that was playing on the boom box in the dining area and to enjoy the company of the true climbing heroes: the Sherpas. For decades their people had risked their lives to fix lines, carry supplies, and guide climbers to the top. No one forced them into their profession—they loved it, and many of them saw it as not only a job but also a passion.

I had great respect for them as individuals and as professionals, yet there was a sense of cultural inequality that made me uncomfortable. It didn’t feel right that they would drop everything to help us and constantly call us “sir” or “ma’am.” I certainly appreciated the help and the honor they gave us, but I would have rather interacted with them on equal terms.

I listened as the Sherpas told story after story about relatives who had died climbing Everest or other mountains. But none of them seemed deterred.

As a trekking Sherpa, Pumba didn’t have as high of a risk as

the Sherpas who went to higher altitudes, but he still had to be away from his family for long stretches.

“Why do you do it?” I asked him.

He shrugged. “Well, sir, I make money for my family,” he said. “I want my son to go to university. I want him to get a good job one day.”

I turned to Pasang. “What about you?”

“I always dreamed of standing on top of Chomolungma,” he said. “Very high honor.”

Then Pasang turned to me, changing the subject. “Are you feeling ready for tomorrow?”

I nodded my head. “As ready as I’ll ever be.”

Then it was time to head to my cold, dark dungeon for some rest.

The following day we woke up early and prepared to move to Lobuche, a small village at an elevation of 16,000 feet. I’d been hoping for a hot shower, but the pipes were frozen, so I was out of luck—and probably would be for another couple of days. As we ate breakfast, I heard the distinctive sound of whipping blades. I looked out the window and saw that one of the members from another team had to be evacuated by helicopter because of some form of edema. It was a reality check about how quickly things can go wrong at this altitude and how important it is to recognize and respond to the warning signs before it’s too late. It was also a reminder about how quickly some people are willing to bow out.

We left Pheriche and followed the meandering trail for a few miles through desolate, rocky terrain leading to some gradual hill climbs. At one point I looked over at Bill and saw that he was hunched over, standing off to the side of the trail. After losing his breakfast, he kept walking as if nothing had happened. We climbed to 15,000 feet and had tea at the base of what would be our most significant climb of the day. During the rest time, I found a nasty outhouse to relieve myself in that was only a slight improvement from the “facilities” I’d have as we reached higher elevations—little more than a bucket in a tent. Then I mixed some orange Tang into my water canister and took a few moments to sit and enjoy the view.

Blind Descent

Blind Descent