- Home

- Brian Dickinson

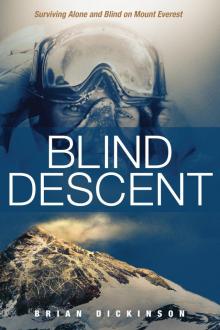

Blind Descent

Blind Descent Read online

Blind Descent is an absolutely gripping, factual narrative of Brian Dickinson’s extraordinary experience on Everest. The story of his descent just after losing his eyesight while low on oxygen kept me at the edge of my seat. This book is emotionally charged and so compelling that I found it all but impossible to put down. Blind Descent is a must-read!

DON D. MANN

SEAL Team Six

Who would have thought Mount Everest would now have two blind climbers? But I got the added pleasure of ascending the mountain blind as well. Brian’s story is a harrowing adventure, a testament to his faith, and well worth the read. I only wish I’d known him before his climb so I could have given him some tips on descending by feel.

ERIK WEIHENMAYER

First blind climber to summit Mount Everest

Personal strength, Navy training, and family support got Brian Dickinson to the summit of Mount Everest. Yet when he found himself blind and alone atop the highest point on earth, it was Brian’s faith that led the way down during his amazing and treacherous blind descent.

JIM DAVIDSON

Climber and coauthor of The Ledge: An Inspirational Story of Friendship and Survival

Visit Tyndale online at www.tyndale.com.

TYNDALE and Tyndale’s quill logo are registered trademarks of Tyndale House Publishers, Inc.

Blind Descent: Surviving Alone and Blind on Mount Everest

Copyright © 2014 by Brian Dickinson. All rights reserved.

Cover and interior photographs copyright © Brian Dickinson. All rights reserved.

Designed by Stephen Vosloo

Edited by Stephanie Rische

Published in association with the literary agency WTA Services LLC, Smyrna, TN.

All Scripture quotations, unless otherwise indicated, are taken from the Holy Bible, New International Version,® NIV.® Copyright © 1973, 1978, 1984, 2011 by Biblica, Inc.® Used by permission of Zondervan. All rights reserved worldwide. www.zondervan.com.

Scripture quotations marked NLT are taken from the Holy Bible, New Living Translation, copyright © 1996, 2004, 2007, 2013 by Tyndale House Foundation. Used by permission of Tyndale House Publishers, Inc., Carol Stream, Illinois 60188. All rights reserved.

Scripture quotations marked NCV are taken from the New Century Version.® Copyright © 2005 by Thomas Nelson, Inc. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

Some of the names in this book have been changed out of respect for the privacy of the individuals mentioned.

ISBN 978-1-4143-9862-4 ITPE edition

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Dickinson, Brian.

Blind descent : surviving alone and blind on Mount Everest / Brian Dickinson.

pages cm

ISBN 978-1-4143-9170-0 (hc)

1. Dickinson, Brian. 2. Mountaineers--United States--Biography. 3. Mountaineering--Everest, Mount (China and Nepal) 4. Snowblindness. I. Title.

GV199.92.D52A3 2014

796.522092--dc23

[B] 2013050916

ISBN 978-1-4143-9576-0 (ePub); ISBN 978-1-4143-9171-7 (Kindle); ISBN 978-1-4143-9577-7 (Apple)

Build: 2015-07-01 14:06:57

I’d like to dedicate this book to my wife, JoAnna, and my children, Emily and Jordan, who make life worth living. I couldn’t ask for a more supportive and loving family.

Contents

Prologue

Chapter 1: Expedition of a Lifetime

Chapter 2: The Long Road to Nepal

Chapter 3: Village Hopping to Base Camp

Chapter 4: Into Thick Air

Chapter 5: Life at Altitude

Chapter 6: Eyeing the Mountain

Chapter 7: Solo Ascent

Chapter 8: Descending on Faith

Chapter 9: Escaping the Death Zone

Epilogue: Life after Everest

Acknowledgments

Notes

About the Author

Prologue

March 30, 2011

Snoqualmie, Washington

THE SKY was a menacing gunmetal gray, with dark storm clouds flowing in and casting an ominous shadow over the snowcapped peaks in the distance. This would have made for horrible climbing conditions, but it was an eerily fitting backdrop for what I was about to do.

The house was blanketed in silence. My wife, JoAnna, was at work, and our kids were both in school. I’d spent the past several weeks cramming in as much family time as possible, playing endless hours of LEGOs with Emily, who had just turned seven, and Jordan, who was four. Now it was finally time. I’d checked everything off my to-do list, and I had the house to myself. It was a moment I’d been thinking about and dreading for months.

In a matter of days, I would set off on my two-month expedition to Mount Everest. It wasn’t the climbing that had me anxious—it was the thought of being away from my family for so long. When it came to the climb itself, I wasn’t worried. I was in the best shape of my life, and I had planned everything down to the last detail. But I was also aware of the reality that people do die on Everest. No matter how well prepared you are, there are always things that are out of your control—extreme weather, shifting icefalls, avalanches, cerebral edema. Let’s face it, there’s a reason they call the top of Mount Everest the death zone.

As the winds picked up and rain began pelting my office window, I cast one last glance at the darkened face of Mount Si, which was slowly disappearing into the Washington mist. Then I sat down at my desk and powered up my MacBook. After I’d centered myself in the video frame, I took a deep breath and hit Record. I could already feel the tears burning behind my eyes.

“Hello, JoAnna,” I began, a sob catching in my throat. “If you’re watching this, something must have gone terribly wrong, and I’m in heaven now, watching you.”

CHAPTER 1

EXPEDITION OF A LIFETIME

“I know the plans I have for you,” declares the LORD, “plans to prosper you and not to harm you, plans to give you hope and a future.”

JEREMIAH 29:11

GROWING UP in the small town of Rogue River, Oregon, I never imagined that one day I would be planning a Mount Everest expedition. My family and I lived in the shadow of the Siskiyou Mountains, and I’d heard plenty of news reports about mountaineering disasters—especially the ones that occurred on the highest peak in the world. I was just a kid in the 1980s, when more climbers began ascending above 26,000 feet on Everest. That translated to more fatalities—and more media coverage. Between 1980 and 2002, 91 climbers died during their attempt to summit.

In 1982 alone, tragedy struck expeditions from four different countries. British climbers Peter Boardman and Joe Tasker disappeared while attempting to be the first to climb the northeast ridge. Then a Canadian expedition lost their cameraman to an icefall, and just a few days later, three of their Sherpas lost their lives in an avalanche. The American team wasn’t exempt from tragedy that year either, as a woman named Marty Hoey, who was expected to become the first woman from the United States to summit Everest, fell to her death. Even a veteran Everest climber from Japan and his climbing partner died near the summit due to extreme weather before the year came to a close.[1]

And then, more than a decade later, disaster struck again when eight people were caught in a blizzard and died on Everest. Over the course of the 1996 season, 15 people died trying to reach the summit, making it Everest’s deadliest year in history.[2]

As a child and a young adult, I was gripped by those stories, but it seemed insane to me that mountaineers would climb in such arctic and oxygen-deprived conditions. Why would people want to risk plummeting to their death or losing body parts to frostbite? Like most people, I was a victim of the media. Although only 2 to 3 percent of those who attempted to summit Everest l

ost their lives, the news seemed to report only the fatalities. Everest seemed like an impossible death trap that only a few elite individuals could conquer. And even then, they’d remain permanently damaged—physically or mentally—as a result of the experience.

But while I may not have had visions of climbing the tallest peak in the world one day, I was a very daring kid. I started participating in extreme sports as soon as I was old enough to venture out without supervision. Now that I’m a parent myself, I realize how much stress I put my parents through—especially my mom. My schedule was packed with organized sports like soccer, baseball, track, golf, and tennis. In between I rode my single-gear bike everywhere. On any given day in the summer, I would ride 10 miles away to the Rock Point Bridge, where I’d leave my bike in the ditch on the side of the road and jump off the 60-foot bridge into the mighty Rogue River.

My best friend, Joe, and I used to climb to the top of the peaks surrounding Rogue River and play a game we called “no brakes” on the descent, which basically entailed running as fast as we could down the steep hills and jumping over any rocks in our path. I’m not sure how I managed to make it through my childhood without breaking any bones, but I certainly spent a lot of time with scraped-up limbs and skin that was swollen from poison oak.

One day when my parents were gone, I took a dare from my older brother, Rob, to ride my bike off the back of the bed of my dad’s old rusty truck. I high centered on the tailgate and fell headfirst into the gravel, ripping up my face. I ended up needing stitches under my nose and in my mouth where the skin had ripped away from my jaw. My face was a massive scab for a few weeks, and I could only drink from a straw.

That didn’t stop me from seeking out extreme adventures though. Whenever I saw a hill or even a big dirt pile, I felt some innate desire to conquer it. During my senior year in high school, I went camping with my parents in Mammoth, California. While everyone else was fishing, I decided to head out by myself with some cheap rope to scale the rocky peaks, like I’d seen people do on TV. I successfully climbed one and decided to rappel down, using the belt loops on my pants as my harness. Not such a good idea.

As soon as my body weight tightened the line, all six loops snapped loose, and I was fast roping down 30 feet without gloves—meaning there was nothing holding me to the rope except my two bare hands. As I strolled back into camp with bloody friction burns on both hands and all my belt loops flapping, my parents just shook their heads. After years of having me return from various adventures with cuts and bruises all over my body, it took a lot to surprise them.

•

Now, almost two decades later, I still had the same inner drive to push myself to extremes, but I’d matured along the way and gained a healthy respect for mountains. On top of that, I’d learned a lot about climbing techniques, safety protocol, and proper equipment. No more belt-loop adventures for me.

It’s hard to trace exactly when my love for climbing began, but it may have been the ascent I made as a teenager to pour my grandma’s ashes on the top of the mountain facing her house.

She and my grandpa lived across the creek from my family, so I spent a lot of time at their house when I was growing up. When I was 14 years old, Grandma was diagnosed with cancer and went through a series of aggressive chemo treatments. The treatments didn’t help much; they just made her last few months miserable. One of the last times I saw her, she was sitting on the couch with a little head scarf covering her frail head. She waved me over to the couch, and I sat down beside her.

Pointing with her bony finger at the mountains outside the window, she leaned close to me. “Brian,” she whispered, “I want you to sprinkle my ashes on top of that hill.”

She was sure she was about to die, and even though I knew it was coming, I wasn’t ready. My family was going to San Diego to see my brother graduate from Navy boot camp, and I was afraid she wouldn’t be there when we returned.

I was right. After the funeral, my best friend, Joe, and I headed up the mountain with the box of her ashes. When I reached the top of the mountain, I made a cross out of some tree limbs, poured her ashes on the ground, and said a silent prayer. Then Joe and I ran down the mountain in our normal “no brakes” fashion, most likely in an attempt to make things as normal as possible and to avoid the awkward emotions that were rising up inside me.

I took my climbing to the next level when I ascended Mount Rainier for the first time in May 2008. A friend and I signed up with a climbing group, and I was both excited and nervous to explore at a higher elevation than I’d ever been to before. I was also eager to learn some technical knowledge about glacier travel. Leading up to the expedition, I trained on Mount Si, a smaller peak near my house, and when the time came for our adventure, I felt ready.

During the three-day expedition, our group learned various mountaineering skills, including rest steps, pressure breathing, rope travel, and self-arrest. I was surprised how strong the wind could be as we made our way to higher elevations, but it wasn’t enough to stop us. It did slow us down, though, and it felt like for each step forward, I took one step back. I felt the rise of nausea in my throat, and my muscles were screaming, but I was confident I could do it. I put my chin down, placing one foot in front of the other, and suddenly we were there. We’d made it to the top! By the time I made it back to sea level, it was official. I was hooked.

After climbing Rainier several times, I summited other mountains in the Cascade Range, including Mount Shasta in California and Mount Baker in Washington. Mountain climbing tested my physical abilities and mental sharpness like nothing I’d ever attempted before. And even though I’d grown up surrounded by mountains, being on top of them gave me a newfound appreciation for their grandeur. There’s just something about standing at the top of a mountain that’s like no other feeling in the world. It’s hard to describe, but a sense of complete calm comes over me as I try to take in the beauty and vastness of God’s creation.

In the past decade of climbing, I’ve gotten one recurring question from people who don’t climb: “Why do you do it?” The reasons for climbing are unique to each individual, and if you were to ask 20 different climbers the same question, you’d likely get 20 different answers. For me, it mostly comes down to the way God has wired me. I have a deep drive to set big goals for myself and then strive to achieve them. If I don’t, I feel like I’m not living life to the fullest and becoming the person God created me to be.

I’ve also found that climbing provides a spiritual solitude that I haven’t experienced anywhere else. There’s something about being up there on the mountain heights that shows me the vastness of God in a way that’s hard to comprehend when my feet are on level ground. While I respect the mountains, I truly respect and am humbled by the Creator of those mountains. As I’ve studied Scripture over the years, I’ve discovered that mountains are mentioned about 50 times in the Psalms, so I must not be the only one who thinks they give us a glimpse of God’s majesty.

You are glorious and more majestic

than the everlasting mountains.

PSALM 76:4, NLT

Now that I’m a husband and a father, I get even more questions about why I climb. But honestly, I think that having a family makes me a better climber because it gives me an even greater sense of responsibility. That’s not to say anything against climbers who don’t have families, but I think that there’s a unique kind of accountability that only mountaineers who are parents can understand. My faith and family always come first, so when I’m determining which peaks to summit and what climbing situations to put myself in, I always factor in my values. I pray about it and discuss it with JoAnna. Then, if I feel like God is leading me to go on a certain climb, I break my goal into achievable chunks to figure out what it would take to make it happen.

If I determine that the goal is selfish and would have a negative impact on my family, I scrap it. There are plenty of peaks around the world I’d love to climb, but I’ve abandoned them before I even got started. I knew

that although they might have provided some sense of accomplishment and satisfaction, they would have taken away from family relationships and ultimately just fueled a compulsive drive to climb another mountain.

Here is my golden rule in climbing: I will never abandon my family. I had no idea how much that rule would be tested on the top of Everest on May 15, 2011.

•

Part of the reason I found myself on Everest that unforgettable day can be traced back to a simple conversation I’d had with a friend several years before. During a perfect summer night in 2007, my family and I were at the home of my close friend, Adam Henry. My kids, who were about the same ages as the Henry kids, were playing in the playroom upstairs, and our wives were at the table talking to each other.

Adam and I knew each other from work, and we’d already gone on some adventures together, such as rappelling, snowboarding, and mountain biking. But we’d never done any mountaineering before, so it felt completely out of the blue when Adam said to me, “We should do the seven summits!”

At the time, I hadn’t even heard the term seven summits, and I didn’t even recognize the names of most of the mountains he mentioned. I found out that in the climbing world, the seven summits refer to the highest peaks on each of the seven continents. Dick Bass was the first to climb all seven summits in 1985. He came up with the idea together with Frank Wells, who at one time had been the president of Walt Disney Company. But in the 20-some years since, only about 200 people had successfully completed the task, which made the challenge all the more compelling in my eyes. Plus, it combined a few of my favorite things into one dream: travel, audacious outdoor goals, and adventure.

I barely hesitated before responding. “Done!”

Of course, the reality wasn’t as simple as my one-word answer that night. It wasn’t something I wanted to decide flippantly.

When JoAnna and I talked about it, her initial response was, “Okay . . . but even Everest?” She shook her head, knowing that I was serious and that I’d probably already mapped out the whole trip in my mind. We talked about what it would mean for me and for our family, and we spent a lot of time praying about it and making sure it was the wise choice for us at this point in our lives.

Blind Descent

Blind Descent