- Home

- Brian Dickinson

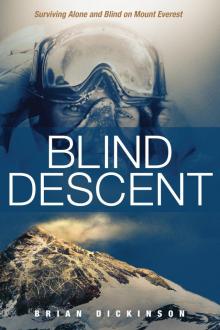

Blind Descent Page 21

Blind Descent Read online

Page 21

Our plan was to get down to base camp, call our wives, and then head down to Pheriche. We’d figure out our next steps there depending on how my eyesight was doing. My right eye was already starting to clear up a bit, but my left eye was badly damaged, and I was struggling to see straight.

I’d learned in first-aid training for AIRR that eyes work in coordination, as the muscles try to keep both eyes aligned. That’s why we were taught to cover both eyes in an eye injury. For example, if a knife were stuck in a victim’s eyes, we’d cover both of them, since if one eye moves, the other moves with it. Now I was on the other side of my training—as the one with the injury, not the one treating it.

We ate an early dinner of dal bhat and then retreated to our individual tents, where we staged our gear for an early morning departure.

I lay in bed until well after dark, too excited to sleep. The reality of what I had accomplished was finally starting to sink in. When you plan and dream about such an event, you never really understand the true magnitude of the challenge. And when it finally becomes a reality, it feels utterly unbelievable. As both the traumatic events and the climactic moments replayed in my mind, I sobbed throughout the night, filled with a mixture of gratitude, joy, and delayed fear. I had compartmentalized my emotions to get down the mountain alive, and now the compartment had burst wide open. The tears were welcome, painful as they were—and so was sleep, when it finally came.

•

Around 4 a.m. Bill and I were both awake and ready to move. I got dressed for the descent and finished packing my gear. I slowly crunched across the frozen snow and staged my pack near the cooking tent. The darkness gave my eyes some relief, but I felt searing pain anytime an occasional headlamp pointed in my direction.

Bill and I sat on a cold slab in the tent while Dawa warmed water for drinks. After a quick breakfast, I thanked Dawa and gave him a tip, knowing it might be the last time I saw him.

“Thank you for everything,” I said, giving him a hug. “I’ll miss you.”

“Congratulations on summit, Brian!” he said, thumping me on the back. “Go back home to see your family.”

I picked up my pack, strapped it around my waist, and headed down the hill.

I started moving more efficiently as the vision in my right eye gradually returned. I tried keeping my right eye open and my left one closed to help with equilibrium, but I still felt off balance. I needed to stay alert, because the Western Cwm is littered with hidden, snow-covered crevasses. It was more important than ever for me to stay close to my team and listen for their warnings.

The first half of the trek was pretty straightforward, but I knew that as I got closer to Camp I, I would have to cross ladders and crevasses and eventually descend the 30-plus ladders through the Khumbu Icefall. Much too soon, the sun started to peek out over the mountaintops ahead. I was wearing Pasang’s extra pair of tinted goggles, but I knew it wouldn’t be enough to protect against the midday sun. I picked up the pace, trying to move as quickly as possible under the circumstances.

Then we came to a step-over crevasse measuring a couple of feet across, 20 yards wide, and hundreds of feet deep. I grabbed the fixed rope and connected my safety as a precaution before easily stepping across.

I could feel gravity on our side as we made our way downhill, and perhaps the even greater advantage was the decreasing altitude. With each step lower, the air thickened, filling my lungs with life and energy. Every step is bringing me closer to home and my family, I kept telling myself.

The first ladder I approached on the Western Cwm was a single, with one fixed line to help with balance. Since my equilibrium was still off, I relied purely on feel to get across. Each step was like a puzzle to solve, with the points of my crampons gripping the aluminum rungs. I probably would have been better off without the rope, but I held on tightly and bent my knees to lower my center of gravity. With each step, the rope pulled me off center, and my heart kept jumping into my throat.

My legs were shaky, and I certainly wasn’t fast or graceful, but I managed to make my way across. I opted out of the five-ladder crossing and took the 15-minute walk around instead. That route wasn’t easy either, as it circumnavigated the deep crevasse and then switched back and forth through sections that measured just a few feet wide and over 100 feet deep. Any slip there would certainly ruin my day.

•

Entering Camp I felt like a big accomplishment, but it also was a reminder of what was ahead of me: the icefall. We took a quick break for water and a snack and then made our way up and out of the Western Cwm. At the top of the icefall, we had to switch back and forth to avoid major obstacles, so I was clipping in and out of the fixed lines the entire route.

When I reached a crossing that had been made of four ladders the last time I was there, I was relieved to discover that avalanches had wiped it out a week ago and there was now a new route. Instead of having to venture across a bridge of four ladders, we climbed down a series of ladders that were bolted to the ice. Once at the bottom, we crossed a flat section—right through the heart of the crevasse—before climbing up another set of ladders to get out.

I clung to the rope as I found each rung with my crampon points. My spikes kept getting pinned between the rungs and the ice wall, so I had to be cautious when freeing them so I wouldn’t lose my balance and fall backward. When I got to the two tied-together ladders that were leading out of the crevasse, I noticed that they weren’t exactly straight. They slanted to the right, and when I moved to the second ladder, the whole thing swung sideways, barely attached to the ice wall with a single ice screw. I held my lifeline securely and pulled my way to the top, where I stopped to hydrate my parched mouth.

I looked ahead of me, testing my vision. Close objects were becoming more visible through my right eye, but everything beyond 20 feet was still a complete blur. I wanted to be able to move faster, but I knew that frustration isn’t a productive emotion, so I picked myself up, grabbed the fixed rope, and continued toward my destination.

We had to cross a handful of ladders and crevasses, and I was grateful that Pasang stayed near me during this portion of the journey. He crossed the ladders ahead of me and tightened the safety lines from the other side.

When we came to a maze of fallen seracs, I could tell immediately that there was no way around it: I’d have to rappel down. Every obstacle you make it through is one more obstacle closer to your destination, I told myself.

As I came around the final corner to enter the gauntlet of ice, I surveyed the scene, trying to figure out what had happened. From what I could gather, an avalanche of ice must have wiped out that section in the last few days. It looked like a bomb had been dropped in the center of the Khumbu Icefall. Ultimately, though, the avalanche worked to our advantage, because it meant we had a few hundred yards of flat, open walking. This leg of our journey ended up taking us only 15 minutes rather than the usual 45. God, is this another one of your miracles? I couldn’t help but wonder.

In no time, we were through the valley of snow and ice. We’d reached the midpoint of the icefall.

The rest of the way down was uneventful, which is exactly what I’d been hoping for. I got into a rhythm of clipping in and out of the fixed lines and cautiously making my way up and over the fallen seracs. The sun was beaming down in full force, but its negative effects were balanced out by the oxygen-rich air, which was recharging me by the minute. When I reached the end of the ice and the beginning of the rocky base camp path, I felt relief course through my body. As I bent down to remove my crampons, I said to myself over and over, I made it! I really made it!

Images of what I’d seen and what I’d survived flashed through my mind, but I forced myself to compartmentalize them. I was on a mission to get home, and I didn’t want anything to distract me. I figured I’d have plenty of time for that in the days to come.

•

Bill and I radioed down to base camp, letting the Sherpa crew know we’d arrived. Everyone was very excited about my summit and

our safe return. One by one, the crew came up to me, shaking my hand and embracing me. My success was their success, which made the moment special for all of us.

We ate a quick bite and rehydrated before escaping to our tents. My first priority now that my phone had reception was to call JoAnna. I talked to her for 30 minutes, describing every detail of my ordeal. I wished she could have been there in person since I knew there were parts of the story that were hard for her to hear, but I was so glad to finally be able to share this with her.

“I was so worried you were permanently blind,” she told me. “I’m so glad you’re okay.” I heard her ragged breath, and once again I regretted my brief words on Veronique’s phone.

“Now you just have to make it out,” she said.

Emily and Jordan were already in bed, so I asked her to tell them that I’d climbed Everest and was on my way home. I knew I couldn’t tell the kids all the details for years to come since it would only cause them unnecessary concern—both now and when I went on future climbs. More than ever, I wanted to be home to hold JoAnna and the kids tight, to let them know how much I loved them and how thankful I was for them. I would have to wait for five more days.

After I reluctantly hung up, I packed up my base camp gear so the Sherpa porter could start heading down. Our plan was to get down to Pheriche that day, to Namche Bazaar (or farther) the second day, and then fly out of Lukla the following day. It was Bill’s 40th birthday, so the Sherpa team made a birthday cake for him and a summit cake for me. We were in a rush to go, but we didn’t want to be in such a hurry that we brushed past this celebratory moment and the company of our Sherpa crew.

I fumbled around with my camera, trying to focus with one eye open, but between my poor vision and the damage my camera had sustained from the cold temperatures on the summit, the photos didn’t do the moment much justice. The pictures of my cake were little more than a bright yellow blur, but at least I was able to mark the occasion.

Then it was time to say good-bye to our Sherpa family.

“Thank you for all your help and for the great conversations,” I told them, giving each one an individual tip, plus most of my gear—down jackets, pants, and booties. “I will miss talking to you. Please enjoy returning to your families.”

•

As I left base camp for the final time, I turned back, trying to freeze the image in my mind. Remember this! I told myself, willing my mind to memorize every part of the scene.

As I made my way toward Lukla, which would take me to Kathmandu and then to Bangkok, on to Taiwan, and finally home to Seattle, I thought about the final blog post I’d write as soon as I had a chance to sit down somewhere with Internet access. I’d have to write it with one eye closed, but I knew exactly what I wanted to say.

May 17, 2011

First off, I’d like to apologize to JoAnna and my family for putting them through this worrisome two-month adventure. You’ve been very supportive, which I appreciate, but it was a risky endeavor, and I apologize for any pain and worry I may have caused you. What started as a major life goal ended as a fight for survival. I lived to tell about my nearly impossible scenario on Mount Everest only because of sheer determination to live and a miracle from God. . . . With God, anything is possible.[8]

EPILOGUE

LIFE AFTER EVEREST

Everyone who is a child of God conquers the world. And this is the victory that conquers the world—our faith.

1 JOHN 5:4, NCV

AFTER MY 38-mile blind stagger through the Khumbu Valley, the rest of my journey home was a breeze. Many summiteers stay an extra night in Kathmandu and sign the wall in the Rum Doodle restaurant, but I was on a mission to get home as soon as possible.

It seemed surreal, after fighting for every inch of ground, to be covering more than 500 miles per hour while sitting in the back row of a Thai Airways flight. I’d lost 20 pounds, and I looked like I’d just taken second place in an intense mixed–martial arts battle. My eyes were swollen and black, and I had scars all across my face from extended periods of wearing an oxygen mask. Thankfully, my eyes weren’t causing much pain anymore, although they were still sensitive to light. In terms of vision, my right eye still wasn’t perfect, and everything through my left eye was a complete blur. I could see well enough, however, to notice that other passengers would look at me and then quickly avert their eyes.

It’s really over. The thought brought a strange mixture of relief and disappointment—relief that I’d survived, and disappointment that the adventure was coming to an end. I couldn’t wait to see my family again, but there was also some degree of letdown. The moment I’d been planning for, hoping for, and dreaming about for months was firmly behind me. It seemed impossible that I was sitting in a climate-controlled cabin, eating a meal that didn’t involve Spam in any form, and resting without wondering if the walls around me would come down in the wind.

I looked around at the other passengers through my hazy eyes and wondered about their stories. Nobody here knows what happened to me in the past few months, I thought. No one knows I experienced a miracle of Christ a mile into the death zone. As I reclined in my seat, tears filled my eyes. Heavenly Father, I prayed silently, thank you so much for delivering me from death. Thank you for getting me safely on this plane. Please give my family peace as I make my way home. And please restore my vision. Thank you, Lord. Amen.

As I drifted off to sleep, I pictured the scene that would be awaiting me when I returned to Sea-Tac Airport. A group of friends would be there to welcome me, but most of all, I kept imagining running through the airport to embrace my family. My eyes were getting heavy as the cadence echoed through my mind one more time: Emily, Jordan, JoAnna. Emily, Jordan, JoAnna.

•

Once my plane finally landed in Seattle, several hours later than planned due to mechanical difficulties in Taiwan, I was bone tired but also filled with the adrenaline of a much-anticipated homecoming. It seemed to take forever to deplane, but I made my way as quickly as I could through the blurry Sea-Tac Airport.

The escalator to the arrival area was packed, so I raced up the stairs. There, waiting at the top, was my wife, looking more gorgeous than ever. We embraced bashfully, with tears streaming down our faces. Somehow two months apart had made us both more in love and more nervous around each other.

I was jet lagged and hungry, so we stopped at a McDonald’s drive-through on the way home. Under normal circumstances, I’m not a fan of fast food, but after two months of freeze-dried dinners, my burger and fries tasted like a five-star dinner.

When we got home, the kids were sleeping, so I sneaked into Emily’s and Jordan’s rooms to kiss them on their foreheads. They were the most precious sights I’d ever laid eyes on—even more breathtaking than the Himalayan peaks I’d tried to capture with my camera lens.

The next morning, before I was fully conscious, the kids came running into our room to dive-bomb me in bed. Jordan kept staring at me through his long eyelashes, saying, “Daddy, Daddy, Daddy!” over and over again. Emily couldn’t stop smiling as she recounted in detail everything she’d done for the past two months.

After I’d been home for a couple of days, JoAnna let me read her version of my return, which she’d written about in her journal.

May 21, 2011

Brian arrived home very late last night after his plane broke down in Taiwan. A friend came over to stay with the kids while I picked him up from the airport. I couldn’t wait to see him—I’ve never anticipated an event so much in my life. The moment I saw him, everyone around me disappeared, and we held each other for a long time, both of us crying. My husband was finally home!

It was a surreal moment, knowing that he’d been through so much but that I’d been disconnected from most of it. He had come so close to death, and I knew I’d never be able to fully understand everything he’d experienced on that mountain. Nobody would. In that moment, I wasn’t sure I ever wanted him to climb again. I was afraid he’d leave us forever.

•

It took a few days at home before my right eye returned to normal. I had to make a few visits to the ophthalmologist for my left eye, but after about a month, my cornea healed properly, and my vision returned.

My mind has taken longer to recover. I still deal with post-traumatic stress disorder when I give detailed accounts of my story. If I’m discussing Everest at a surface level, I’m able to keep my emotions in check by skipping over or downplaying the more horrific details. But when I give live presentations, I still break down when I talk about certain aspects of the descent.

When I describe my last radio call down to Bill and Lakpa, I’m immediately drawn back to that moment of realization, knowing how close I came to never seeing my family again. And when I tell people about the time I ran out of oxygen at 27,500 feet and how I surrendered completely to God, that’s when I really lose it. In that moment, I was given the gift of life and an unexplained miracle. I don’t understand why I made it when so many others throughout the years have not. It’s too mind boggling to comprehend, and the only thing I can do in response is to live as fully and gratefully as I can.

For someone who’s used to living a quiet life, it feels strange to be thrust into the spotlight, especially since I’m just as flawed as the next guy. But for some reason God spared my life up there, and I’ve been given the task of sharing my story and helping others however I can. I may not feel worthy, but I don’t want to waste the gift.

Ever since my return, I’ve been asked regularly if I’ll keep climbing, and specifically if I’ll continue to pursue the seven summits. I believe that what happened to me on Everest was a fluke—not something I would expect to happen again—and it hasn’t scared me away. Since coming home, I’ve led groups up Mount Rainier, Mount Baker, Mount Shuksan, and other Cascade peaks. I’ve also climbed Vinson Massif in Antarctica and soloed Mount Aconcagua in the Andes mountains, which means I’ve soloed the summit of the highest peaks in both the Northern and the Southern Hemispheres.

Blind Descent

Blind Descent