- Home

- Brian Dickinson

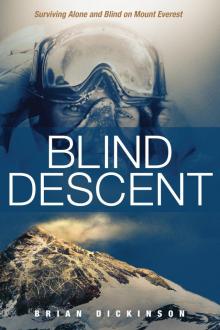

Blind Descent Page 18

Blind Descent Read online

Page 18

I stopped to get another drink from the large thermos in my backpack. I anchored off to an ice screw, took off my pack, and removed my oxygen mask so I could get a couple of sips of water. Then I put everything back on again. I hung my head, exhausted.

The more I thought about the gravity of my circumstances, the faster my heart rate became and the more oxygen I needed to breathe. You need to focus, I told myself. Breathe in; breathe out. I exhaled slowly, turning my mind to the next task at hand: strapping my mask back on.

•

Meanwhile, Bill and Lakpa were heading up toward the South Col, some 3,000 feet below—about five or six hours, under normal conditions. They tried making radio checks every 15 to 30 minutes, and after getting no response, they started to worry.

During a water break near the South Summit, I’d pulled the radio out of my pack and tried to place a call, but all I got was static. I held the radio a couple of inches from my face and squinted to try to make out the correct knobs, but I wasn’t able to read anything. After a while, I decided my time would be better spent trying to get down the mountain. I placed the radio in my pack and didn’t pull it out again.

I continued down from the South Summit to the place where I’d made a video of the sunrise on my ascent. It was hard to believe that just a few hours earlier I’d set eyes on this breathtaking sight, and now I couldn’t see a thing. That’s mountain climbing for you, I thought wryly. You can take a turn for the worse in the blink of an eye.

I had originally planned to grab a couple of rocks from the summit for my kids, but now that was the last thing on my mind. I just wanted to make sure their dad returned to them—and not in a body bag.

I kept heading down until I reached the top of the South Rock Step. At this point I faced a critical decision: should I rappel down the South Rock Step as I would have normally, or should I swing the rope to the left side, down a steep wall of snow and ice?

Rappelling with crampons on a rock face requires precise movements and a great deal of focus. With their steel spikes, crampons are made to pierce ice and snow, not rock. If you don’t wedge a spike into a rock crack properly, you risk slipping off the granite surface. Can I do that based solely on feel? I wondered.

I decided to go down the left side to descend the snowy 70-degree slope. As I contorted my right foot to gain purchase on the steep slope, I suddenly felt a pop as my crampon released from my boot. As if in slow motion, the dark, blurry object toppled down about 20 feet and then stopped on the slope. I wasn’t entirely sure the object below was my crampon, but I had to retrieve it. I couldn’t get down without both crampons—not in these conditions.

“Lord, help me get through this,” I prayed. “Please protect me.”

Trying to remain calm, I took my first step, digging the spikes in my left heel into the thawing snow. I took my next step with the boot that didn’t have a crampon, and as I dug my heel into the ledge, the snow gave way. Unable to break my fall, I tumbled head over heels down the steep slope.

My down suit could only do so much to cushion my flailing body as I bumped down the hill, ice jutting into my side, my back, my shoulder, and my head. I felt my oxygen tank digging into my back as I tumbled. My camera, which I’d tucked into my down suit, was crushing my ribs.

As I turned upside down, my tank slid from my pack but caught on the breathing tube, preventing it from falling thousands of feet down the mountain. Then I felt a major jolt as my safety-rope shock loaded. The weight of my entire body was caught by the extended rope, giving me the worst whiplash I’d ever experienced. My back arched, and my legs and arms bent backward, facing down the mountain. But I was alive. My safety harness and the fixed lines had just saved my life.

I lay there breathing hard, trying to recover from the shock. I’d just fallen down the South Summit of Mount Everest—blind. And so far at least, I was still breathing to tell about it.

My feet were above my head, but I didn’t want to right myself because I was afraid that would cause my oxygen tank to fall out of my pack. Fortunately, I was still getting some supplemental oxygen, even though my mask had been ripped sideways, away from my face. I lay there forcing myself to remain calm and lower my heart rate.

Once again I was reminded of AIRR school. During training, the instructors would have us swim underwater for the length of a swimming pool and then swim freestyle back—and we had to repeat this over and over again, until we almost passed out. If we surfaced from an underwater swim early, the instructors would scream, “Control your breathing!” I’ll never forget seeing one candidate who surfaced for air during a 25-meter underwater swim and then dipped back into the water, struggling to reach the other side without resurfacing. Breathless and oxygen deprived, he knew it would be better to black out and potentially drown than show the instructors he wasn’t giving it everything he had.

As I carefully righted myself, I felt a presence telling me that I needed to get some water. I didn’t hear anything audible, but the words You should take a drink filled my mind. I remember feeling surprised, and I said out loud, “That’s a good idea!”

I couldn’t escape the continued sense that somebody was there with me. I can’t exactly explain it, but it seemed like there was a guiding presence by my side, leading me toward safety. In the moment, I didn’t have time to analyze it, but in retrospect, I have no doubt that the Holy Spirit was with me. I’d never had such a tangible experience of the reality described in Isaiah 30:21: “Whether you turn to the right or to the left, your ears will hear a voice behind you, saying, ‘This is the way; walk in it.’”

I hadn’t been conscious of it, but I was completely dehydrated. To my knowledge, my mouth had never been so dry before, and the water revived me—in body and in mind. After drinking a few sips from my thermos, I squinted my eyes, searching for my crampon. It wasn’t long before I realized the effort was hopeless. I’d probably fallen past it already, and even if I hadn’t, the chances were slim that I’d ever see it unless I stepped directly on it.

I strained painfully through my scratchy eyes, desperately hoping to see something dark against the white canvas, but the bright light of the sun banking off the snow burned my eyes. Then all at once I looked above me and spotted a dark, blurry object.

“Lord,” I prayed, “please let that be my crampon, not a rock.”

I donned my gear and faced the daunting prospect of climbing up to check it out. I punched the toes of my boots into the snow a few times with each step to make sure I had full purchase. After placing my foot down each time, I took three long breaths and then used the safety line to pull myself up.

While still gripping the rope, I approached the object and reached down to feel it. Through my thick climbing gloves, I felt something sharp. I held the object close to my face. Sure enough, it was an even row of steel spikes!

“Thank you, Lord!”

Double-wrapping the rope around my arm, I stomped out a small one-by-two-foot platform to stand on as I put my gear back on. I took extra care tightening both crampons and weaving in the extra webbing of the straps to ensure I didn’t trip on it. Then I slowly started traversing back to the safer rocks.

Not far from my platform, as I sidestepped toward Nepal, the earth below me broke loose into a small slab avalanche—the shifting that occurs when a block of snow breaks loose from a fracture and slides over the layer below. I immediately dropped into a self-arrest position, with the fixed rope in hand. Self-arrest—a method used to stop a fall—is typically done with an ice axe in hand, not a fixed rope. The idea is to roll and drive your ice axe into the snow while kicking the front points of your crampons. I didn’t have my ice axe above Camp III, but after years of training, it was automatic to assume the position.

I rode out the fall in a glissade style—squatting and sliding down in a crouched position—all the while grasping the line as tightly as I could. I was going down so fast that the rope burned a line in my thick leather glove. I felt the sting of the friction burn and

screamed out in pain, but at least I managed to stop my fall.

I lay sideways in the snow, again focusing on reducing my oxygen intake and rapid heartbeat. Even with the arctic temperatures, I was sweating profusely inside my down suit. I couldn’t believe how much more exertion everything took now that I was short one of my senses.

The fall put me down lower on the South Rock Step, but I still had to get beyond the slippery slope. Although the granite surface was a blur, I was able to distinguish it from the snow. As I slid my hand down the fixed line, I reached an anchor and took a quick rest before connecting again.

I sensed the voice telling me again, Brian, you should get some water. I went through the process of removing my pack, coming off oxygen, and getting out my thermos. Then, out of nowhere, a stroke of genius hit. Why not put your thermos in the inside pocket of your down suit? Of course! It would optimize the process of getting a drink, and it would require much less energy each time.

I connected my jumar to the fixed line above the anchor, dropped my safety on the rope below, detached my jumar, and headed down the rock wall. The whole way, I held on to the rope with the fingers of one hand wedged into the carabiner and my other hand either on a rock or on the rope. I had to make sure that I had three points of contact on the ground at all times and that my crampon points stuck into cracks and flat areas of the rock. Easier said than done. Usually I blindly slid my spikes down the surface of the rock until they caught. In some cases they never caught, so I pulled myself back up and had to find another route down.

It was an agonizing process, and with each step, my mouth grew more and more parched. I had to stop often to quench my thirst, and I was grateful that my thermos was more accessible now.

The last section of the South Rock Step left me with a choice: I could do a large jump-type rappel, or I could do a sideways traverse. Both options had drawbacks. If I rappelled down, I risked falling straight down. If I went sideways, there was the potential that I’d pendulum back and smash into the rock surface. I decided to climb sideways, since a direct fall could result in broken bones, whereas swinging back might result merely in massive road rash.

I moved slowly to the side, basically hugging the rock to control my descent. Normally I would have been worried about ripping my expensive clothing, but at that point I didn’t care one bit if my suit was shredded by the time I finished. I made it across safely and rewarded myself with a swig of water.

I had descended about 1,000 feet from the summit by this point, which felt like a significant accomplishment. But it was concerning, too, because that meant I was only one-third of the way to high camp.

On the little ledge below the South Rock Step, I tried checking my oxygen regulator. I brought the device about an inch from my right eye and tried to focus. From what I could tell, it seemed like I had about 5 percent left, but I couldn’t be sure. All I knew was that the oxygen wouldn’t last long, and I’d need to swap out my tank as soon as I reached the canister Pasang had left at his turnaround point.

As I started down a snowy ridge, the exhaustion of having climbed for almost 28 hours straight hit me. I was completely drained of energy, and I desperately wanted to sleep. It took a lot more energy than I could have imagined to do this without my sense of sight, but I kept forcing myself down the mountain. I walked with tiny steps and relied on the fixed lines, hand over hand.

Eventually I reached a familiar location: the platform where Pasang had turned back. I actually might have passed right by the spot, but thankfully the blurry bright orange object sticking out of the snow caught my attention. The spare oxygen bottle!

The platform area wasn’t much bigger than a kitchen table. I remained attached to the fixed lines but dropped my pack so I could swap out the oxygen bottles. I popped off my face mask, since it would cause suffocation when I disconnected the regulator. For a moment the reality of my situation hit me: I was at 28,000 feet, off oxygen, unable to see, and faced with the prospect of making it to the South Col on my own.

I detached the old bottle but kept it in my pack so I wouldn’t leave trash behind. Then I ran my gloved fingers over the top of the new bottle and screwed on the connector. I brought the regulator inches from my face, hoping to see the blurry black indicator line all the way to the right, which meant full. From what I could tell, though, the line was pointing to the left. I decided to put the mask on to test it. I breathed in, and there was absolutely no flow of oxygen. I ripped the mask from my face.

Okay, let’s figure this out, I thought. I disconnected the tube and cleared the ice away from the bottle. Then I reconnected again, but still no success. My mind raced. I knew I didn’t have enough oxygen in my old tank to make it down. I felt panic setting in. Breathe, I coached myself for the 100th time that day.

I could see only one option: I’d have to make do with the current bottle and get as far as possible, then go without supplemental air. I reconnected the original bottle and took in some much-needed oxygen. Well, you can’t sit there and troubleshoot all day, I told myself. I placed the other bottle in my pack and set out again. The extra bottle added 15 pounds to my pack, but it was ingrained in me not to leave trash on the mountain, so I headed down with less oxygen and more weight.

For the next part of the route, I had to cross the snowy ridge—the one I’d punched my feet through the night before. I moved with great caution, hugging the right side. As the day wore on and the sun grew brighter, the pain in my eyes became almost unbearable. It felt like rocks were scratching the inside of my eyelids, and no matter how hard I fought to keep them open, they threatened to shut of their own volition. My feet were heavy and clumsy, my legs felt like dead weight attached to my crampons, and my throat was constantly parched. I kept swiveling my head and squinting, trying unsuccessfully to find any blurry landmarks that would help me estimate my location.

At one point, at the height of frustration, I stopped, held the rope tightly, and yelled, “I will not die on this mountain!”

I felt tears welling up involuntarily. “Stay strong!” I coached myself. “Push forward—you will survive!”

I kept moving. The path started to open up a bit, and I approached a large, blurry rock formation. I recognized the flat area and position of the rope anchors. I was at the Balcony—halfway back to the South Col! You’ve made it this far, I told myself. You’re going to survive.

When we’d made our original plan, Pasang had said he would wait for me at the Balcony. But since I was much later than planned, and the wind was picking up on the unprotected Balcony, I figured he must have decided it would be safer for him to head back to the South Col. I’d keep making my way down solo.

I sat down on a flat rock, closed my eyes, and felt myself drifting off to sleep, so I quickly stood up. I ate a handful of trail mix and drank some water. I wondered what everyone below was thinking by now. I wasn’t sure what time it was, but I knew I’d been on the mountain a lot longer than planned. I had renewed energy, though. I will not become another Everest statistic! I knew there were more than 100 bodies still high on the mountain from failed summit attempts. Maybe that was the one advantage of my blindness: I wouldn’t be able to see them even if they were mere feet away from me.

Before I headed out again, I took a moment to pray. “Heavenly Father, thank you for bringing me this far. I know you’re with me, and I believe you’ll get me to safety. Please, Lord, watch over my family, and help them not to worry.”

I wondered what JoAnna and the kids were doing at that moment. I knew JoAnna was at a scrapbooking retreat that weekend and was probably starting to wonder how I was doing, since she knew I’d be attempting the summit that day. I thought about Emily and Jordan, who were probably sleeping, without a worry in the world.

JoAnna and I had met 16 years ago—in a hot tub, of all places. We both lived in the same apartment complex, and one night she and her friends happened to be in the complex’s hot tub at the same time I was. She was so intimidatingly beautiful that I couldn�

�t even look at her without becoming paralyzed with inadequacy.

I was 21 years old at the time and in the Navy, having just returned from a tour in the Persian Gulf. She was 20 and getting her psychology degree from San Diego State University.

“What do you do for a living?” one of her friends asked me.

Wanting to impress her with my quick wit, I said, “I’m a plumber.” Then I stood up from the water with my plumber’s crack showing.

Everyone laughed, but JoAnna thought I was a jerk.

But over time, it became clear that God had placed us in that pit of boiling water at the same time for a reason, and she eventually became interested in that jerk. We started going to a small church, Zion Avenue Baptist, together. We were young and had a lot of growing up to do, but our little church was a constant in our life, and it helped give us a solid foundation for our relationship.

JoAnna is deathly scared of heights—we couldn’t be more opposite in that way. On her 25th birthday, I wanted to do something she’d never forget, so I took her up in a hot air balloon. She was terrified at first, but as dusk fell, we stood together watching the sun set over the ocean. Then she turned around to see me pull out a diamond ring. Between the flame bursts that kept us in the air, I said, “JoAnna, I love you, and I want to be with you forever. Will you marry me?”

I expected her to burst into tears of joy, but instead she started laughing. Then she said yes and threw her arms around me. After that she was so preoccupied with her excitement that she didn’t even think about her fear of heights.

Did I make a mistake by deciding to attempt this? It was the first time I’d really started to second-guess my decision. But even as I stood at one of the highest points in the world, snow blind, alone, and exhausted, I knew I would never have been content with a lifestyle of sitting on the couch or squelching my ambitious goals. I believed that life was for living. I didn’t want to take unnecessary risks, but I wanted to embrace the big dreams that burned inside me. I also wanted to be a role model for my kids about what it looks like to accomplish what you set out to do.

Blind Descent

Blind Descent