- Home

- Brian Dickinson

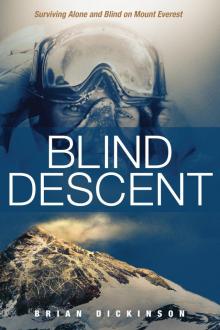

Blind Descent Page 14

Blind Descent Read online

Page 14

Bill and I carried our crampons and planned to put them on before we started climbing over the fallen seracs. As I walked through base camp, I slipped on the snowy rocks but quickly caught myself. I was grateful for the quick recovery; I would have hated to have to abort my summit attempt mere feet from my tent.

When we got to the edge of base camp, I looked over at Bill in time to see that he was vomiting again.

I was getting more concerned. “How are you doing?” I asked.

“I don’t feel sick,” Bill responded, wiping his mouth. “I just needed to throw up.”

We put on our crampons and climbed through the icefall for the seventh time of our expedition. We agreed to go at our own pace and meet up at Camp II. Lakpa and Pasang would meet us there the following day since they wanted an additional day of rest down at base camp.

When I arrived at Camp I for a break, I sat in one of the shared tents we used for acclimatization, careful to not puncture the vestibule with my crampons. I opened a cattle feed bag, which the Sherpas had used to cache our food and supplies. To my surprise, the Sherpas had left a few Mars bars in the bag for me, and I stashed them in my pack for later use.

Then I decided to melt some snow for drinking water. It was difficult to keep the stove lit at such a high altitude with strong winds, so I had to use my body to protect the cooking area. I filled a cooking pot with snow and then placed it on the flame. Since snow is made mostly of air, it took several pots of snow to fill up my canister.

After getting enough water for Bill and me, I left Bill’s portion in the pots. Then I wrote a note in the snow by the tent so he’d know where to find the water. I put my pack on again, reapplied sunscreen, and continued my journey toward Camp II.

When I approached the first major crevasse in the Western Cwm, I passed a man who was missing a leg and was wearing a modified crampon on his prosthetic foot. He was alone and moving slowly, but the look of determination on his face was unmistakable. I didn’t know if he was going to Camp II or whether he planned to continue higher, but I was confident he’d reach his goal. I was inspired by his drive and his desire to overcome significant challenges. Even without a disability, climbing a mountain is a daunting task. I couldn’t even imagine attempting it without the use of all of my limbs.

As he and I prepared to cross one of the ladders, we exchanged greetings.

“Beautiful morning!” I said.

“Yep.” He didn’t have much to say, and I could tell he was focused on the task at hand.

“See you up there,” I said. “Be safe.”

The sun was scorching, so I stripped down a few layers and applied additional sunscreen. At this point in the expedition, my skin was the darkest it had ever been, despite my constant reapplication of sunblock. At this high altitude, there were a lot more direct rays that came into contact with my skin. And since the sun reflected off of the snow and ice, it was easy to get burned in places that didn’t usually see the sun—like the underside of my arms, the bottom and inside of my nose, and the inside of my ears.

In addition to the sunscreen, I wore a buff to protect my vulnerable face. The downside to the buff is that it filtered the air, and at that elevation, you need as much air as possible. I had little choice, however, because without it, the sunscreen wiped off every time my nose ran.

I was also careful to keep my goggles on. Not only did they protect my eyes from the blinding sun reflecting off the snow, but they also helped guard against UV rays. Since the atmosphere is thinner at higher elevations, it absorbs less ultraviolet radiation. In fact, ultraviolet radiation levels increase by 10 to 12 percent with every 3,000-foot increase in altitude.

In true Everest form, it went from being blazing hot one minute to whiteout blizzard conditions the next. Fortunately, another group that had gone before me had marked the route with wands, so I was able to find my way. Even though the snow was coming down in furious gusts, I was still hot from the penetrating sun. I continued to hike in a short-sleeved shirt, and I unzipped the side vents of my pants.

Halfway through the Western Cwm, I passed Dawa, our Camp II cook. He said Bill had radioed him, asking him to descend to Camp I to help carry his pack. Dawa was all smiles and offered me juice and chocolate. I thanked him but declined, since I still had my own arsenal of snacks and water.

I was less than a mile from our camp, which according to reports we’d heard from other climbers, had been destroyed days earlier due to high winds. Our Sherpa team had been able to salvage our tents and supplies, but it would take some time to rebuild camp.

By the time I arrived at Camp II, I was exhausted and eager for a break, so I went into the cooking tent to have a snack. After resting for a while, I walked out to where our tents lay collapsed in the snow. I put the tent poles together one at a time and stacked them on the canopy of the tent. I threaded each pole through, taking frequent breaks to make sure I didn’t overexert myself.

I erected the tent, placed the protective fly over it, and anchored all the corners with deadman anchors. For the deadman anchors, I dug four holes, buried snow stakes in each, and then packed snow on top. This was critical for creating a firm hold when the snow froze.

Bill, Veronique, and her climbing Sherpas arrived an hour or so later, and we ate a lunch of hot soup, tea, and Spam sandwiches. The dining tent was a large eight-person tent with a couple of poles in the middle to keep it upright. The seats were made of flat rocks, which we lined with Therm-a-Rest pads for comfort. In the center of the tent there was a stack of rocks, which we used for a table, and the perimeter was lined with additional rocks for the stoves and our cooking supplies.

It had been a big day, so we took it easy the rest of the afternoon. Our personal tents had all been spared from the strong winds, but some of the shared tents were shredded, and our bathroom tent was gone. Thankfully, Dawa rebuilt it later in the day.

I post-holed over to my tent, creating fresh tracks in the deep snow. As soon as I unzipped the door flap, I fell onto the unrolled pad. With my feet still poking out of my vestibule, I removed my crampons and boots and then placed them inside, where I’d have easy access to them. Then, to ensure that no snow or ice would get inside, I stuffed my gaiters inside the boots.

After blowing up my air mattress, I set my –40-degree sleeping bag over the pad. As my last step in setting up house, I placed a picture of JoAnna and the kids in a transparent mesh pocket on the ceiling of the tent. As I lay on my makeshift bed staring up at their photo, I thought about how much I missed them. I knew it was impossible, but I wished they could experience some of this with me.

Our two rest days at Camp II were pretty low key, and we basically just went through our normal routine of relaxing in our tents and eating regularly scheduled meals. I also took advantage of the downtime to analyze my pack. I was using my heavy 95-cubic-liter pack, and I was concerned it would be too heavy at higher elevations. At such high altitudes, every ounce matters. I decided to do some investigative surgery, and when I opened up the lining of the pack, I found metal plates inside for back support. Since I would only be carrying a couple of oxygen bottles, I decided to remove the plates. I tried the pack on again, and I could tell a difference in the weight immediately. I only wished I’d thought of this weeks ago.

I spent most of my time in my tent listening to music, reading, and looking at pictures of my family. It seemed like an eternity ago that I’d been hugging them and listening to my kids’ stories about their day at school. Now I was as far away as possible—on the other side of the earth, and higher up than most people could even imagine. Still, I was excited to finally be making my summit push.

As I thought through each scenario for the days ahead, the eagerness I felt was tinged with a sense of caution. I was about to climb into an unknown world, and I had no prior experience climbing above 23,000 feet. Those realities weighed on me. The only thing I could do was rest in the confidence that I’d prepared for this. I had to trust that my body would respond the wa

y I hoped it would.

Back in AIRR training, the instructors’ goal was to wreck us completely in simulation exercises so that the emergency situations themselves would seem easy by comparison. After doing full-body conditioning all morning until we could barely stand up, we’d head to the ocean or the pool for mile-long swims or other intense conditioning. Then we’d swim sprints and perform buddy tows, all while wearing full rescue gear (a harness packed with rescue devices such as knives, flares, and strobe lights), a rescue vest, fins, a mask, and a snorkel. We’d also have to tread water while holding bricks and simulate every worst-case scenario imaginable. Each day we asked ourselves why we were doing this, but after it was all over, we knew we’d be ready for anything.

•

On May 13 I awoke to hear Bill and Dawa talking in the cooking tent. I crawled out from the comfort of my warm sleeping bag and put on my layers, ready to climb to 23,700 feet. I deflated my air mattress and stuffed my sleeping bag into its compression sack. Then I checked my pack to ensure that there were no air pockets and that the weight distribution was balanced. If something was off kilter even a little bit, I would feel one side of my body aching partway through the climb.

When I walked into the cooking tent, I saw Bill hunched over on one of the rock slabs we used for seats. He informed me that he’d vomited during the night and still felt queasy. After a short discussion, we decided it was better for him to take an extra day at this altitude to let his body heal.

After breakfast, I headed up toward Camp III; Pasang would follow me up about an hour later. It was cold as I made my way through Camp II and onto the upper half of the Western Cwm. I pulled out my handheld video camera and recorded my ascent through camp. I couldn’t stop smiling—and it wasn’t just for the camera. I was finally making my way into position for a summit attempt! The reality was starting to hit me, and I couldn’t hide my excitement.

I made it to the base of Lhotse Face relatively quickly and cached my trekking poles to the side of the main route. When I arrived at the bergschrund, I connected my safety devices to the fixed lines and started making my way up the ladder. A couple of Sherpas were coming down the ropes on the right side, so I connected to the left side, which was essentially a steep overhang of ice. It took a lot of effort to inch my way over the first obstacle, and I had to kick hard to gain solid purchase into the rock-hard ice. Once I made it to the top, I rewarded myself with a quick rest and a drink of water, and then it was time to continue my steady pace toward my destination for the day.

When I first arrived at Camp III, I had no idea which tent was ours. Pasang told me it was on the opposite side of the fixed lines from where we’d camped on our previous acclimatization climb, but that didn’t narrow it down much. I made my way around a couple of tents, being careful to remain clipped into the safety lines that wove around the icy ledge. A group of Sherpas was watching me, and I realized I must have looked hopelessly lost. How does someone get lost at 23,000 feet in the air? I wondered with a wry smile.

I finally came across a tent that looked similar to the ones we’d been using, so I unzipped it. To my surprise, I found some climbers I didn’t know sleeping inside. Not wanting to feel like a burglar sneaking around in pure daylight, I decided to find a flat platform on the side of the icy face and wait for Pasang.

While I waited, I fumbled through my backpack, looking for some water. I glanced down just in time to see a lone Sherpa making his way up the mountain and figured it must be Pasang. Then I looked to my left and saw a pile of oxygen bottles, a bundled tent, and my ice axe. Sure enough, I was sitting on the platform where we would set up camp.

When Pasang reached my location, he sat down and took a brief rest before we worked as a team to erect our four-season tent. At this elevation, building a tent took a great deal of energy. Just putting the poles together required us to do pressure breathing, where you purse your lips and force the carbon monoxide out of your lungs to make them more ready for an exchange of oxygen.

Once the tent was built, we cooked dinner: tomato soup and ramen noodles. We then watched as a group of guys attempted to ski down Lhotse Face. They appeared to be roped up, and they had their ski poles fitted with ice axe picks. They took the descent really slowly, knowing that one slip could result in an uncontrolled fall and almost certain death. Since the weather was fluctuating rapidly, they would ski for a bit, stop, and then start up again. It was taking them a long time to get anywhere, and I grew tired of lying there with my head poking out of the vestibule, so I burrowed into my sleeping bag and drifted off to sleep.

There’s something about sleeping with oxygen that provokes extremely vivid dreams. All through the night I was transported to my childhood, reliving adventures and camping trips with my family. In one dream, I was in Mammoth, California, with my older brother, Rob, and my sister, Lisa, and we were all climbing rocks and fishing. I heard my dad playing “Barracuda” by Heart at an obnoxious volume, and I could even smell the clean scent of the pine forest. I was young and didn’t have a care or worry in the world. Then I woke up and remembered where I was. I was climbing to the summit of Mount Everest!

The next morning we heard rumors about a Japanese man who had died near the South Summit. Although there were a lot of speculations, we weren’t sure of the exact cause of death. As I always tried to do, I prayed for the victim’s family—that they’d come to a place of understanding despite the pain. I didn’t know this man’s specific circumstances, but it was a sobering reminder about the need to be humble in the shadow of this mountain.

I never wanted to have a “summit or die” attitude; in the end, it’s a mountain, and no mountain is worth dying for.

•

On May 14 we headed up to the South Col, where the highest camp in the world is located. We were entering the death zone. To get there, we had to climb straight up Lhotse Face for about a mile and then cut over at the Yellow Band, a section of layered marble, phyllite, and semischist that looks yellow against the stark whites and grays of the rest of the mountain. Then we had to traverse up and over the Geneva Spur—a rib of black rock that requires an angled climb.

The entire route was equipped with fixed lines, which made it safer but also meant that each step required significant effort, due to the constant steep angle of the climb. All your movements feel like they’re in slow motion, and you have to preserve your energy as much as possible. I tried to find a steady pace and then stick with it. It’s like running a marathon at that point—you don’t worry about if other people are ahead of you or behind you; you just keep plodding along.

About 1,000 feet above Camp III, I stopped to get some water. I anchored myself to an ice screw with some cordelette and a carabiner attached to my harness. As soon as I set my anchor and tested its integrity, I pulled off my goggles, which I looped through my arm, and then removed my oxygen mask. Right at that moment, my crampon slipped on the unstable ice. To break my fall, I automatically reached for the fixed line with the hand that was holding my goggles. In a flash, my goggles slid off my arm and fell down the steep face. I watched in horror as my eye protection escaped into the abyss of ice.

It seemed the goggles were sliding down the mountain in slow motion. And I didn’t have a backup pair. If you’re doing an intense climb like Everest, you simply don’t have room in your pack to bring extras of anything—and whatever additional gear you take means extra weight you have to carry with you.

Down the mountain to the right, there was a vertical field of ice with several open crevasses, and my goggles were heading straight toward it. Then, miraculously, they curved back to the left and were stopped by the Sherpas going up the fixed line. I let out a breath, not even realizing I’d been holding it in.

A group of Sherpas who were heading up to Camp III grabbed the goggles. They motioned to me that they had them and that I could come down and get them. I was so relieved that they’d been able to stop them from descending farther, but that meant I’d have to retrace my steps an

d hike back down 500 feet. Still, it was worth it to have something to cover my vulnerable eyes.

Pasang was a little ahead of me, so I shouted up to him, “Pasang, I dropped my goggles. I’m going to rappel down to get them.”

“That’s not good,” he said. “Be careful. I’ll go to the South Col and make tents.” Pasang continued his slow ascent up the hill.

I secured my pack, including my oxygen bottle and my mask, to the anchored ice screw, took a couple of breaths of oxygen, and rappelled down the face to retrieve the goggles. It was easy going down since gravity was on my side, but I knew going up would be more of a challenge. As I got close to the rope where the Sherpas had attached the goggles, I slowed down to make sure I didn’t accidentally dislodge them from the fixed rope. When I reached out to untie the knot, I noticed that the goggles were cracked right through the middle of the inside lens. The outer lens was still intact, leaving only one layer for protection against ultraviolet rays. I didn’t have too much time to think about the implications, though, so I put them on, connected my jumar and safety line, and headed back up without the use of supplemental oxygen. When I arrived at my backpack, I took a couple of hits of oxygen and then donned my full gear again.

At that moment I knew I was up against a challenge. The instant I turned on the regulator on my oxygen mask, my goggles fogged up. Goggles tend to get a little foggy at such low temperatures under normal circumstances, but usually you can use your gloves to scrape away the fog or ice. Now, with a crack through the center of the goggles, they were freezing between the layers. That meant I couldn’t see out of them, and there was no way to clear them. I tried wearing my sunglasses instead, but with the oxygen mask strapped across my forehead, I couldn’t keep the glasses close enough to my face to stay on. During the rest of my journey to the South Col, they were so iced over that I could only see through a dime-sized circle on the left side of my goggles. I focused all my attention on the fixed lines, knowing how critical each step was for my safety.

Blind Descent

Blind Descent