- Home

- Brian Dickinson

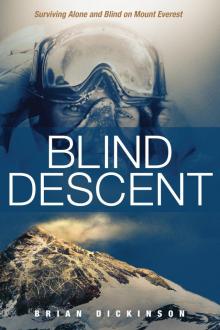

Blind Descent Page 11

Blind Descent Read online

Page 11

It was extremely cold and windy up at Camp I, but I barely noticed. I was so excited to be this much closer to my goal. The summit of Everest is visible from only a few locations throughout the Khumbu Valley, but from where I stood in that moment, I had a clear view. After so many years of reading books, hearing stories, and watching movies about Everest, I was finally here, in the shadow of the real thing. It felt surreal—the mountain was right there, yet it still seemed a universe away.

I saw other climbing teams and Sherpa porters heading up the great valley to Camp II, and I wished I could join them. But I knew my time would come. For now I needed to listen to my body and be patient.

•

Hoping to get relief from the wind, Pasang and I rested for a few minutes behind a tent, where we ate a quick lunch of bread, hard-boiled eggs, cheese, fruit, and juice boxes. It was the best meal I’d had in a long time. After lunch we decided to head back down to base camp before the sun heated up the path and made things unstable. Despite the assistance of gravity, going downhill wasn’t that easy, since we still had to negotiate our way through the ever-changing icefall. One area had seracs the size of a two-story house leaning against each other. As we made our way between them, it felt like we were walking down a very narrow hallway—a cold one, at that. I knew the formation wouldn’t stay in place much longer, so I tightened my helmet and hurried through the tunnel to avoid getting crushed.

The next challenge Pasang and I faced was rappelling over an ice cliff with ropes anchored to a pair of aluminum pickets. I made sure to double-check the anchors, locking the carabiners and webbing and checking for any weak or frayed areas. It wasn’t ideal, but with two anchors, I felt confident that even if one broke, the other would catch.

Back home, I led Extreme Adventures rappelling events for my church, but that was much easier since I didn’t have all the gear that was required on Everest. At our church events, I wore shorts and light hiking boots, and I didn’t have a 50-pound pack on my back.

My crampons stuck to the ice, slowing my momentum, and the rope slipped back and forth on the ice-pivot area. Finally I was able to make my way down safely. After crossing several more ladders, this process started to become more comfortable for me, but I knew I needed to guard against becoming complacent. After a long day, it’s easy to get sloppy and make mistakes—in fact, most accidents occur on the way down.

And even when you’re on high alert, things can still go wrong. Just as I was making my way across a crevasse where three ladders were tied together, I experienced one of a climber’s worst nightmares.

As I carefully placed my crampons on each rung, I kept a firm grasp on a single fixed rope. Then, when I was in the middle of the ladder, the rope suddenly came free of its anchor. I lost my balance but tried to stay calm, kneeling down to lower my center of gravity. I grabbed hold of the rungs with both hands and then carefully inched my way across without a safety line.

“Thank you, God,” I breathed as I reached the other side.

I’d heard stories of climbers who had fallen into crevasses below, and their bodies weren’t found until years later, when they were churned out by the glacier miles from base camp. And during my 2009 Denali expedition, one of our team members in the middle of the rope tripped on some bulletproof glacial ice. He fell straight on his ice axe and ended up breaking several ribs.

I was determined to keep focused on each step. I knew I wouldn’t be safe until I was back in my tent.

I’d learned a lot about the importance of focus during my Navy days. In the second week of AIRR training, we were put through an extensive lifesaving course, where we learned techniques to gain control of active survivors in emergency situations. The first thing we had to do was force the survivor deep underwater, which usually causes panicked survivors to panic more and release control, making it easier for the rescuer to get the upper hand after they surface. But since this was AIRR training, we were learning worst-case scenarios, which meant the instructors who were role-playing the survivors never released control. We dove deep with the latched-on survivor and then applied various pressure points to turn the victim’s back toward us. That would enable us to lock control with a cross-chest carry.

A lot of candidates were weeded out during this portion of the training. They simply weren’t able to stay calm underwater for long periods of time. In one particularly intense training session, I was attacked from behind by a survivor. I brought him deep underwater until he was in a state of panic, and then I turned him around and gained control at the surface. But I’d missed one pressure point—a specific spot near his elbow.

The instructor, who was underwater evaluating me, took me to the side of the pool and let me know where I’d gone wrong. “Airman Dickinson, you failed the rear head hold release procedure,” he barked. “You have one more chance to pass, or you’re gone!”

I nodded, closed my eyes, and pushed off the side of the pool to tread water. In a split second, I was hit by a force that felt like a refrigerator being dropped on my back. Someone was gripping tightly around my neck, forcing me underwater and making me inhale lungfuls of water. Without panic or hesitation, I pulled three hard strokes, bringing us to the bottom of the pool. I felt a gag reflex coming from my throat as a result of the water I’d breathed in, but I forced myself to remain focused on my task.

I could feel the survivor struggling to get to the surface, so I bent forward, loosening his hold, and grabbed his arm, which was wrapped around my neck. I pulled straight down to break his hold. Meanwhile, I gripped his wrist with my right hand and slid my left hand to his elbow. My fingers landed on the pressure point, and I heard a painful exhalation of bubbles escape from the survivor’s mouth. I rotated his arm over my head, released his elbow, and locked him in a cross-chest carry with his wrist still pinned behind his back. I kicked my fins hard to propel both of us to the surface, where we took in some much-needed air. I kept a strong grip as I forced the water from my lungs in exchange for oxygen. Looking left to right to ensure my path was clear, I saw the instructor slowly nodding his head and giving a thumbs-up. I’d passed lifesaving.

And without realizing it, I’d gotten some invaluable preparation for being on a mountain one day, where focus is a life-or-death issue. Gratefully, I made it down the mountain safely and without incident. I planned to rest at base camp for a few days before heading back up to Camp I.

On Easter, I called JoAnna. I knew that she and the kids would be having dinner with friends back home.

“Hi, honey!” JoAnna said. “Let me put you on speaker so you can talk to everyone.”

I was met with a chorus of greetings from the kids and from our friends. “How are you doing?” they asked.

“Great!” I said. “I’m about to head up to Camp I through the Khumbu Icefall. How’s everybody back home?”

Just as they started to respond, I saw that Pasang was gathering our supplies. “I’m so sorry,” I said. “I have to hurry up and get moving. Happy Easter!”

Then I talked directly to JoAnna. “I love you, sweetie. Tell the kids I love them too.”

“Be careful,” she said, as she always does. “We love you!”

•

Before we began our trip, Bill and I had agreed to climb on our own schedules. We would stay together when possible, but neither of us wanted to feel like he was impeding the other person’s success. Since Bill had been sick, he was now one day behind me in the acclimatization process. Pasang was pulling double duty, heading back to Camp I with me and then returning to base camp to help Bill. That meant I’d be spending the night alone at Camp I. I planned to continue up to Camp II with Lakpa the next day, and then we’d descend all the way back to base camp. This would push my body to adapt to higher elevations and then force it to produce more red blood cells when I rested back at base camp.

That morning’s climb through the Khumbu Icefall was uneventful, and I could tell I was stronger than I’d been my first time through. I didn’t get winded t

hroughout the entire trek to Camp I, even though my pack was heavier this time. I was now transporting my high-altitude gear, which consisted of my –40-degree sleeping bag and my down suit. Although the down suit was awkward to carry with me, I knew I’d be grateful to have it once we got nearer to Camp II. The suit covered my entire body and was made of 850-fill down feathers, which made it essentially like walking around in a sleeping bag.

As we walked, Pasang monitored my progress. “You are very strong,” he told me. “You should only need to go to Camp II once to sleep. Then you can climb to Camp III.”

My mind was racing: After that, I’ll sleep on supplemental oxygen at Camp III . . . and then I’ll be ready for the summit!

Halfway through the icefall, we crossed paths with Dave Hahn, who was leading a group for a Seattle-based guiding company.

“Hey, Dave, how’s it going?” I shook his hand, both of us still in our climbing gloves. “I’m your Everest base camp neighbor.”

“Hey, man! We’re just coming down from our first rotation at Camp II.”

“That’s great,” I said. “Have a safe trip.” I made my way to the next ladder and clipped into the fixed line.

“See you at camp,” he said as he headed back to check on his clients.

I didn’t mind the quietness of the climb with just Pasang and me, but it was nice to see another friendly face along the way.

With the recent avalanches and the seracs that had collapsed from Lola Peak, the icefall had already changed since I was there just a few days earlier. When I arrived at one of the crevasses, I saw that it had widened, requiring four ladders instead of three. That may not seem like much, but with each additional ladder, the platform becomes increasingly unstable. I started across one of the newly expanded crevasses, and with each step I took, I could feel the ladders dipping down with the weight of my body. I felt the entire temporary bridge swaying slightly, first to the left and then to the right. I was relieved to step off the ladders and onto the slightly more stable ground.

It wasn’t long before we came to a couple of sections where we’d need to do some ice climbing. These spots would have been easier with ladders, but we’d have to make do without. We squeezed through tight ice walls and front pointed our crampons to climb over the looming seracs. I was grateful I had the right gear for this. My crampons had come equipped with steel spikes on the front (front points), which I forced into the ice for stability. Essentially I was relying on my foot protection to hold me as I used anchored ropes to haul myself up a 15-foot wall of ice. I could only imagine the horrific damage that could occur if I was in the wrong place at the wrong time under one of those massive ice blocks.

At one point, when I was crossing a two-section ladder and standing on the third rung, a Sherpa accidentally let go of my fixed rope handle. I lost my balance and stepped backward off the ladder. As I stepped back, my crampons struck the shin of one of the Sherpas who was standing behind me. I felt awful and bent down to look at his leg and make sure he was okay. Thankfully, his skin had barely been punctured.

“I’m fine,” he assured me with a smile. “It wasn’t your fault.”

When we got to Camp I, Pasang boiled water for hot tea, and we ate a boxed lunch of meat, cheese, fruit, and bread. As I was setting up my tent, he dropped off a few propane stoves, fuel, and food for future meals since I’d be cooking on my own after he headed back down the mountain. I was glad to have a handheld radio in case something went wrong, but I wasn’t really concerned about my solo camping adventure.

Before Pasang descended, I had an important question to ask him. “Is there a safe place to use the restroom?”

Everything was pretty exposed at the top of the icefall, with nothing but seracs and open crevasses surrounding the tent.

“Yes.” He pointed toward the icefall. “Be careful!” Then he disappeared into the river of falling ice.

I set up my tripod and filmed myself doing some interior decorating in my tent—blowing up my inflatable mattress and setting out my sleeping bag. I wanted to document my journey for my family so they would have at least some idea of what this experience was like. I managed to inflate the mattress without passing out or getting light headed, so that seemed like a good sign. However, it did take considerable effort just to set up my tent and get my sleeping area ready—something I wouldn’t have even noticed at lower altitudes. That’s high altitude for you—simple tasks take triple the effort.

After I drank a few liters of water, it was time to break the seal and depart from my cozy tent so I could explore the area Pasang had pointed out. Just three steps away from my tent vestibule was a step-over crevasse that was so deep I couldn’t even see the bottom. I could see how someone who fell into that crack in the middle of the night would never be heard from again. To prevent injury, I grabbed a bamboo wand with a piece of red tape on the end—a makeshift flag—to mark the danger. I also dropped off an empty Gatorade bottle at my tent so I wouldn’t have to venture out in the darkness if I needed to relieve myself. I walked toward the other tents to find a narrow area to cross and eventually found a spot that functioned as a primitive outhouse.

After returning to my tent, I realized I was ravenous, so I ate some trail mix and a candy bar. I ticked off the most common symptoms of acute mountain sickness in my head: headache, nausea, lack of appetite. I was eating enough food for three people, which I took to be a good sign. My metabolism was burning through food almost as quickly as I could chew it, so I continued indulging in carbs and fats.

Since I had some downtime in the afternoon, I decided to get some film footage for my sponsors. I brought my tripod, camera, and mini-high-definition video recorder and tried to get video with Everest in the background. After I started filming, I noticed that some of the climbers who were camping 30 yards below me had come out of their tents to watch me record myself. I wasn’t expecting an audience, so the attention made me a little nervous. I did a few takes and figured I could edit them later. The wind was picking up, and the temperature was dropping, so I wrapped up and returned to my tent.

I’d brought along a sealed card from JoAnna and the kids to open on Easter. It seemed like so long ago that I’d talked to them, even though it had been earlier that morning. There was something about knowing it was a holiday that made me miss my family even more than usual. I opened the card in the solitude of my tent.

Happy Easter! We are so proud of you. We miss you, and we can’t wait for you to come home. We love you so much!

Love,

JoAnna, Emily, and Jordan

Tears streamed down my face as I sat there alone, wishing with almost every part of my being that I could be home to celebrate with them. But I quickly realized that crying in the high altitude created intense pressure on my head, so I willed my tears to stop.

The wind outside picked up, and I could feel the wind thrashing my tent, so I decided to stay inside and watch The Empire Strikes Back on my mini-laptop. It was a much-needed distraction to lose myself in a story other than my own for a few hours. I bundled up in several warm layers, snuggled into my –40-degree sleeping bag, and finally drifted off to sleep.

•

The higher elevation dramatically affected my body’s chemistry and fluid balance—a condition called altitude diuresis—which meant I had to get up four times that night to empty my bladder. The urine in the bottle froze almost immediately, which made for an interesting night. After each use, I had to melt and pour out the contents a few feet from the tent so the bottle would be ready for the next time I woke up.

When I awoke at 5 a.m., it took me a moment to remember where I was. Then reality came charging into my consciousness: I was at Camp I on Mount Everest!

I packed my gear, lit the stove, and boiled some melted snow for coffee (I was careful to make sure it was the nonyellow variety). Then it was time to prepare my freeze-dried breakfast: two bags of seafood noodles and one kimchi noodle package. As I forced down the last few bites, Lakpa showed up with

supplies for Camp II. He had a cast-iron cooking stove and a couple of oxygen bottles strapped to his back, which likely totaled more than 100 pounds. I had been expecting him to arrive at eight o’clock, and it was only seven. How does he do it? I marveled. I quickly got my things together, and five minutes later we were on the trail.

The route to Camp II wasn’t too difficult, as it followed the Western Cwm for a couple of miles, up to 21,300 feet. We negotiated across a handful of ladders, most of which we crossed uneventfully. We did encounter one crevasse that was so wide it required five ladders tied together, end to end. There was, however, an optional 15-minute walk-around, and I usually took that route. I crossed the five-ladder crevasse only once to get a picture. The moment I stepped on the first ladder, it dropped about a foot and started swinging from side to side. With each shaky step, I had to balance by gripping the safety lines and taking slow, deliberate steps while keeping my eyes fixed on each rung. Beneath me I saw hundreds of feet of glacial blue ice that disappeared into a deep, black abyss.

Through the rest of the Western Cwm, Lakpa and I moved efficiently, which is the term for “fast” in mountaineering, but for the last half hour of our journey to Camp II, it felt like we were in slow motion. I felt fine physically and wasn’t having trouble breathing, but even so, at that altitude, your pack feels heavier and your body moves more slowly.

For the first time the whole trip, I saw Sherpas stopping to catch their breath. They’re human after all, I thought. It felt frustrating not to keep up a fast, long stride and a steady pace, but it was a good opportunity to practice my rest step—not to mention patience.

The rest step feels unnatural, and it requires a conscious effort to take a step, shift your weight, and pause for three seconds before taking another step. But I knew it was the wise thing to do if I was going to reach my destination. Instead of counting to three during the pause, I silently recited the names of my family: Emily, Jordan, JoAnna. Step. Emily, Jordan, JoAnna. This mantra gave me a constant reminder of my priorities, and in some small way, it felt like they were there with me, cheering me on.

Blind Descent

Blind Descent